Rosa!

How Veronica Moreno hated that name … well, at least disliked it. She loved roses, mind you, that was her favorite flower, and she had even asked for a rose-print dress for her recent twelfth birthday. But she resented Rosa Vargas, while at the same time she would have basked in the reflected glory of being her best friend. In fact, all the girls in her grade would have—and of course, the boys.

As you probably have guessed by now, thirteen-year-old Rosa Vargas was strikingly beautiful. Not only that, she was articulate and gifted with a winsome personality. She was destined to go places and everyone knew it, especially her parents, the principal, and her teachers, and after whatever function Rosa attended, people effused about her.

Veronica, together with Imelda, Nina, and Elena—three of her Mexican-American elementary school friends—designed and edited a monthly family-friendly color magazine called The Vine, titled after the initials of the four girls’ names. It contained informative commentaries on life in their neighborhood along with short stories, satire, poetry, cartoons, and human-interest contributions garnered from classmates and friends. Dr. Marcia Alvarez, the school principal, being so impressed with the magazine’s absorbing, varied content and artistic design, granted the girls free use of the school’s highly developed printing facility to produce as many copies as needed. The Vine’s suggested price was three dollars, and the team would sell it door to door. Fifty percent of the proceeds went toward paper and printing costs and the rest they divided between the team and the contributors.

Shortly, Veronica and her friends persuaded Rosa Vargas to be—as they put it—their “face to the world” in promoting the magazine. It worked; Rosa believed in it, and sales skyrocketed. To the editing team’s chagrin, however, most customers commented more on the beautiful girl who sold it than on the magazine’s content.

After a while, even though people generally showed more interest in the magazine itself and subscribed to it, many of them would ask after Rosa, which fostered further jealousy among The Vine team and even some of the contributors.

“I-I’m not sure if Rosa Vargas should represent us any longer,” Veronica said in a hushed tone at one of the team’s meetings, which were held every Wednesday afternoon after classes in a corner of the school’s library. Rosa was not present. “People aren’t talking about The Vine, just her.”

“I agree,” whispered Imelda. “It cheapens our product’s profile.”

“Claro,”1 said Nina. “We should be selling it on content alone.”

“Exactly,” said Elena. “It doesn’t need a pretty face to push it.”

“So nobody commented on my feature article?" A wiry twelve-year-old Mexican boy asked. "Only on the girl who sold them the mag?”

“I’m so sorry, Pablo,” said Veronica. “It was a fantastic article. You’re one of our best contributors. Even Dr. Alvarez says so.”

“I still suggest we diminish Rosa Vargas’ profile,” said Imelda.

“Si,” said Nina. “Let’s leave her out of this from here on out.”

“I agree,” said Elena. “Let the magazine fly on its own merit.”

As much as she was inclined to agree, Veronica began to have reservations, and she did not know why.

Meanwhile her grandmother, Doña Lupita, who owned a vineyard south of the border in Baja California’s Guadalupe Valley, invited her to spend the entire six weeks of summer vacation with her.

Consequently, Veronica suggested to Imelda, Nina, and Elena that they wait until she returned before addressing the possibility of ousting Rosa Vargas. They reluctantly agreed.

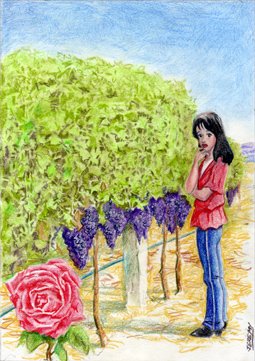

Wearing a satisfied smile, sixty-year-old Doña Lupita, accompanied by Veronica, strolled up and down in the lazy late afternoon Mexican sun between her vineyard’s rows of grapevines.

“It should prove to be a good harvest this year, querida,”2 she said, turning to her granddaughter. “So far, weather conditions have been ideal for a good vintage wine crop. Just a couple of months to go.

“And this is my prize vine,” she said as they entered the last row. “The most abundant, beautiful, and delicious of grapes—rich, hearty, and they do yield the best bouquet in the glass. Beautiful, don’t you think?”

Veronica shrugged. “I wouldn’t know what constitutes a beautiful vine, abuela,3 but the roses planted at the beginning of each row must be the biggest, reddest, and most beautiful I’ve ever seen. And their perfume is just heavenly. Especially the one on this row.”

“That is true, querida. But do you know why we plant a rose at the beginning of each row of vines?”

Veronica shrugged.

“Well, one reason is for ornamentation, because of course the roses do look nice. But a more important reason is…”

Someone called to Doña Lupita from the house about a telephone call, and she hastened off, leaving Veronica, who continued her stroll.

“Psst!”

Startled, the girl turned at the hiss that came from within the grapevine. She peered into the leaves, imagining that someone was hiding in them. No one was there.

“Don’t be scared,” a voice said. “But it’s me, the vine, talking.”

Veronica was tempted to run away, but the vine continued. “Por favor, do stay for a couple of minutes. We want you to do us a favor.”

“A favor? And what is that?”

“We want you to cut down Rosa.”

“Cut down who?”

“Rosa, who is standing at the head of our row.”

“Who’s that? I don’t see anybody.”

“Her, the rose, of course.”

“The rose? Why? She … I mean, it’s beautiful.”

“Precisely. We vines are getting sick and tired of people like you who come and visit the vineyard, and always remark on Rosa’s beauty and perfume and never appreciate our fullness and wealth of taste.”

“Well, my grandmother does. She said so herself, … you heard her.”

“Si. Well, she’s the only one, because she knows all about grapes and vines, and we are her pride and joy. Besides, she’s old. We just want a chance for people to see only us, and remark on our attributes.”

“Hmmm,” said Veronica. “I still think it’s a shame to cut down the rose, though.”

“Listen. Don’t you know how it feels? ‘Rosa this … Rosa that. … Isn’t she gorgeous?’ and so on.”

“Actually I do. There’s a girl who my friends and I work with to promote our … oh, it doesn’t matter. Anyway, she has it all—you know … looks and everything. Well, she at least knows how to talk. Strangely enough, her name happens to be Rosa. Everyone wants to be her friend, including me to be honest, when quite frankly, I wonder if some of us girls secretly wish she would get fat and ugly.”

“There. You see? You understand. So, will you do it for us, por favor? Cut down Rosa?”

Veronica bit her lip and dithered a little. Finally, she nodded.

“You’ll have to do it under cover of night, though,” said the vine. “It mustn’t be obvious.”

“I’ll try,” said Veronica. “But I suppose I could still keep her in a vase.”

“No, no, no, child. Doña Lupita should never suspect. Best thing would be to bury her.”

At that moment, Doña Lupita walked up and informed Veronica that she needed to visit a sick relative up in Tijuana and would not return for about ten days.

“No, no!”

Veronica awoke one morning to hear her grandmother raising her voice in the downstairs hallway. She had just returned from her visit.

“You mean to say our best vine is destroyed?”

“Si, señora. In just a few days. By the time we noticed that its rose was gone, it was too late. The blight had got ’em all.”

“Its rose was gone? How?”

“Seems like someone cut it down.”

Veronica threw on her robe and dashed down the stairs to face her distraught grandmother.

“I’m so sorry, abuela,” she blurted tearfully. “I did it.”

“Did what?”

“I cut down Rosa, … I mean, I cut down the rose.”

“What on earth for? To put in a vase?”

“It’s … er … difficult to explain. …”

“Well, for whatever reason, querida, the damage is done. That was very foolish of you, and maybe I should take the blame for not explaining. We plant those roses at the head of each row of vines to protect them. You see, because roses are so delicate they are the first to show if insects, diseases, and blights are attacking. In effect, the roses die to save the vine crop. In this case, there was no rose to manifest any disease. My workers couldn’t detect it, and consequently my best vine perished.”

“So how did everything go?” Veronica asked her Vine companions upon returning home after the summer break. “The mag and all?”

“Well,” said Imelda, her face falling, “the one we put out while you were gone contained a controversial and rather inappropriate non-family friendly article that Pablo wrote about the ostracism of Mexican-Americans in the U.S. That probably would have been okay in itself, but the problem was that besides some graphic details, he said that we suffer worse than any other ethnic group. Oops! Rather stupid of us, actually, considering our mag’s profile.”

“The situation made news,” said Nina. “Papers, television, and even YouTube.”

“Anyway,” said Elena, “because the mag is produced by a group of elementary schoolgirls, it came under such an attack that we were almost forced to discontinue it.”

“Almost?” Veronica asked.

“Well, guess who saved the day and the mag?” said Imelda. It was easy for Veronica to guess. Rosa Vargas.

“It’s a good thing you suggested we waited on phasing her out, Veronica,” said Nina. “She took the whole brunt, she stepped up to face those cameras and reporters, and, like it or not, she got through to the toughest watchdogs!”

“Then for the next two weeks,” said Elena, “articles and responses flooded in from all over swearing solidarity with The Vine and its stand for constitutional freedom of speech.”

Veronica smiled. Especially in the mouth of one as persuasive as Rosa’s, she mused, and suggested that they—including as many contributors as possible—throw a little party in honor of Rosa, to which Imelda, Nina, and Elena enthusiastically agreed. It turned out to be a most jubilant affair that took place in the school library with Dr. Alvarez’ permission and presence, and one in which all jealousy dissolved with every grateful hug bestowed upon the overwhelmed Rosa Vargas.

And Veronica Moreno, who was so thankful that she had not agreed to “cut her down,” actually did become her very best friend.

The End

Footnotes:

1 claro: (Spanish) clearly, surely

2 querida: (Spanish) darling, beloved

3 abuela: (Spanish) grandmother

See “Cut Down Rosa Supplement” for additional material in teaching the following learning objectives:

—Recognize that jealousy, envy, a desire for more material possessions, coveting what others have, not being satisfied with what one has, and negative comparisons, are all attitudes that show a lack of and need for contentment. (Character Building: Values and Virtues: Contentment-2d)

—Recognize thoughts that are rooted in jealousy, envy, covetousness, greed, and discontent, and the negative effects such thoughts can have on one’s happiness; learn what steps to take in order to practice contentment once again. (Character Building: Values and Virtues: Contentment-2e)

Authored by Gilbert Fentan. Illustrations by Jeremy.

Copyright © 2011 by The Family International